Milepost 35

There’s been a lot of talk on how Nimrod got its name. In the Book of Genesis, Nimrod was the grandson of Noah and he was a mighty hunter and a king. Looking at newspaper clippings in the late 1800s and early 1900s the name Nimrod was used as a synonym for hunter in many articles in Oregon. The McKenzie River Valley and surrounding area has always been a great destination for hunters and fishers so most likely the community was named because of that.

There’s been a lot of talk on how Nimrod got its name. In the Book of Genesis, Nimrod was the grandson of Noah and he was a mighty hunter and a king. Looking at newspaper clippings in the late 1800s and early 1900s the name Nimrod was used as a synonym for hunter in many articles in Oregon. The McKenzie River Valley and surrounding area has always been a great destination for hunters and fishers so most likely the community was named because of that.

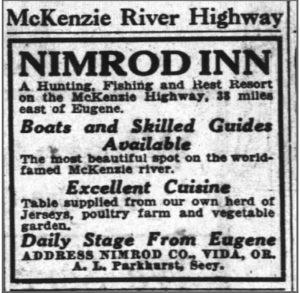

The Nimrod Lodge was opened in the early 1900s on the south side of the river. Their guests had to cross a ferry and later a bridge to stay. The Nimrod Inn advertised electric lights, a piano, and milk-fed chicken dinners. It was one of the more popular destinations on the McKenzie River for a very long time. Today, there are still some of the most relaxing inns on the river in Nimrod. The gas station and general store closed down, but there is still boat ramp and some great fishing in the area.

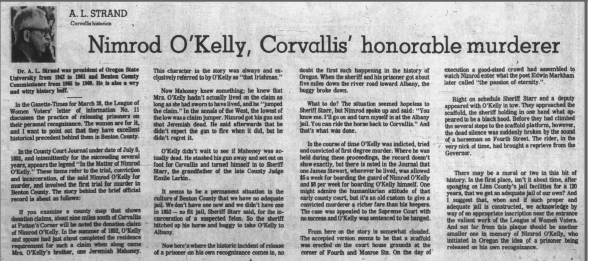

Another theory on how the town of Nimrod got its name is a lot more colorful. The story has to do with a catholic priest who was also the first person to ever be convicted of murder in the Oregon Territory. This murder case was responsible for the very first time the Oregon Supreme Court convened. Some believe that that Billy Price named his inn after Nimrod O’Kelley, one of Oregon’s first homesteaders.

Nimrod O’Kelly was born in April of 1780 in Tennessee. He came to Oregon in September of 1845 and settled a claim around what is now Benton County. O’Kelly had claimed 640 acres of land under the Donation Act. A single person could only claim 320 acres, but O’Kelly claimed the other 320 acres in his wife’s name, but his wife hadn’t yet arrived out west. As the years went by other settlers started to believe that O’Kelly didn’t have a wife at all. One of these men by the name of Jeremiah Mahoney moved onto the far side of the 640 acres staking his own claim with his family.

The day that Nimrod O’Kelly heard this he decided that Mahoney was jumping his claim. He loaded his gun, rode straight to Mahoney’s home, and without a word exchanged shot him dead with buckshot. After doing so, O’Kelly rode straight to Marysville (Corvallis today), found the sheriff, and told the whole story. He turned himself in. At the trial there were no witnesses called and no evidence other than O’Kelly’s own story. At the end of it, O’Kelley was convicted of murder and sentenced to hang.

Due to legal delays that may have been from a legal system not fully developed, the final date of the hanging came down: June 9, 1854, exactly two years from when this all started. Doctor T.J. Wright, the sheriff of Benton County had a predicament. The hanging was almost a year away and the town didn’t have a jail built yet, so he did the only thing he saw fit, he told Nimrod O’Kelly to go home until he was to be hanged. He is reported to have said, “Go home and stay there. I won’t have any use for you until eleven A.M., June 9. But be here punctually then.”

From October 1853 to June 8, 1853, Nimrod O’Kelly lived at his house under his own recognizance. He had returned to the sheriff the night before his hanging and the town still did not have a jail, so the sheriff paid for him to stay in a hotel. The next morning O’Kelly ate breakfast and reported, punctually, at 11am. The court had given the sheriff discretion in the way of hanging Mr. O’Kelly sometime between 11am and 1pm, but O’Kelly, being a sixty-three year old man and fixed in his faith, believed he was going to a better place and wanted to get it over with, but the sheriff told him they would wait until 1pm.

Five minutes before Nimrod O’Kelly was to hang, Governor Davis message got to him commuting his sentence from the death penalty to one year in the state penitentiary in Portland. The sheriff procured an express wagon to Portland and employed a man by the name of Bill Gird as guard and escort for O’Kelly. The journey started well enough but by the time they reached Oregon City the wagon had to stop and be repaired. Always eager to meet his fate, O’Kelly decided to keep walking to the penitentiary. He walked through the autumn weather in the Willamette woods thinking the wagon would catch up at any moment. It never did. He crossed the river and waited for hours at an old hotel the wagon was headed to, but they never showed up. At this point Nimrod O’Kelly walked into the state penitentiary, found the superintendent, and told them his story. The superintendent believe O’Kelley to be crazy and turned him away.

That evening Sheriff Wright and deputy Gird finally arrived and filled out the paperwork to get their money for delivering a prisoner. It took a while, but finally O’Kelly was admitted to the penitentiary. He was such a model prisoner that was released two months before his sentence was to be fully completed. In August of 1855, Nimrod arrived back to his land where his family had finally made a home. He also found the widow and children of Jeremiah Mahoney living on the other side of his 640 acres. The Oregon Land Office had awarded them possession of this land. O’Kelley wasted no time. Without enough money for even a horse, Nimrod O’Kelly, at the age of sixty-five, set off walking to the Nation’s Capitol to plead his case. Alone and on foot he journeyed across the country, to the Missouri River, and then to Washington D.C where he, amazingly, won his case. The land was awarded back to him. Then he turned around and walked home.

Nimrod O’Kelly lived on his land and with his family until his death in 1864. He was seventy-four years old. After he died, he willed the land he killed for, the land he walked over five thousand miles for, to the Catholic Church. His wife did the same with her half of the 640 acres.

Nimrod O’Kelly’s story was still popular in the early 1900s. What was not in his story was that Nimrod O’Kelly was a devout fisherman and had even created a lure named after him. These two facts could mean that the Nimrod Inn and by extension, Nimrod, Oregon, was named after this colorful character.